Richard Timperley Bateson 1893-1991

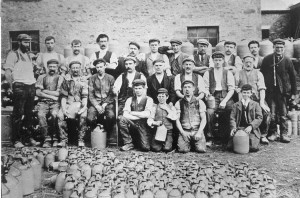

Workers of Waterside Pottery, Burton in Lonsdale in 1910. Richard Bateson is pictured at the front in the middle with his hand over his kneck (He’d broken a button on his shirt collar and didn’t want his Mum to know)

Richard T Bateson began work at the age of 13 in 1907 for William Bateson and sons ltd at Waterside pottery, his father Henry Bateson being joint owner with his Uncle Frank Bateson.

Richard quickly progressed through some of the worst pottery jobs, such as using the jigger jolly machines to produce jam jars to become a very capable thrower. By the age of 17 Richard was capable of throwing every ware that Waterside produced.

Richard took a break from the pottery in 1914 for the First World War. He served in the 5th Manchester. He fought in Gallipolli where he took a bullet in his wrist. He also got injured from a piece of shrapnel in the groin, this meant he was back at Burton recovering when peace was declared in 1918.

Richards’s father died in 1922. Frank Bateson bought out Henry Bateson’s share of William Bateson and sons and continued producing pots until 1933, when the pottery closed. Frank however continued the basket making side of the business, buying in bottles and casing them as well as recasing old bottles. Squire Taylor was employed as Basket maker (or wander as the job was called in Burton). Basket making continued until Squires death shortly after the Second World War.

When Waterside closed Richard then bought Bridge end Pottery (Baggaley Pottery) from Jack Coates. Bridge end Pottery had stood idle for 10 years. The building had suffered neglect during this period. The kiln was in such a bad state that it was deemed unusable. Richard took it upon himself to build a new kiln. This was no mean feet. The kiln he built had an internal cubic capacity of about 10ft square and had four fire mouths.

Richard worked Bridge end for 6 years, producing a full range of earthenware pots, these included various sized plant pots (2.5” to 15”), Jugs (1,2,.5 pint), large milk bowls(mixing bowls) 24” wide, posy rings of various sizes, drinking mugs, teapots, vases. These pots were all produced using mill hill clay. Some of the pots were decorated with slips (ball clay based) and covered in a lead glaze. Sprigged wares were also made. A sprigged blue and white mug and jug made at Bridge end is on display at Lancaster museum to celebrate the 1935 silver jubilee.

Richard sold his wares himself. He travelled about to the larger towns and cities such as Manchester, Liverpool, Lancaster, Preston and Leeds looking for possible outlets for his work. Customers would also turn up at Bridge end and do business with him direct.

During this period Richard only employed a boy to help him. Gordon Booth, and Albert Oversby did this job. One of the jobs required of these boys, on days when it was considered not worth powering up the steam engine, was to manually power a throwing wheel via a small crank situated low down at the front of the wheel. This was not one of the favourite jobs. When John Bateson (Richards’s son) was a child he avoided playing near the pottery, in case his dad pulled him in to the Pottery to crank the wheel.

Richard was struggling to make a living during this time however in 1939 Harold Parkinson of Hornby Castle, a customer of the pottery approached Richard about an idea for making plant pots for Woolworth’s and other similar outlets. The scheme required a larger pottery, so Waterside was leased (from William Bateson and sons) and renamed Stockbridge Pottery (Stockbridge was the name of a mill Harold already owned) with Richard as its Manager. Bridge end pottery was given to Harold Parkinson as part of this agreament. Stockbridge pottery also employed Robert Standing (thrower), Jack Coates (formally of Bridge end. Part time thrower), Charles Brashaw (main taker off for Richard), John Bateson (main taker off for Robert Standing), James singleton (clay miner), Bill Harrison (General worker and Miner), Jack Telford (worker), Charlie Armour (Kiln loader/unloader), Harry Capstick (worker), Tommy Chapels (taker off).

The first major stumbling block encountered was the stoneware glaze recipe used at Waterside for the last 100 years was lost. The man that had mixed the glaze had died and nobody had thought to write it down. The materials to formulate the glaze were known, but not the quantities. In the end a glaze expert from Podmores in Stoke on Trent had to be brought in to sort out the problem.

John Bateson, Richards’s son began work in the Pottery in 1941 at the age of 14. He would have started later, but Tommy Chappels left and Richard needed a replacement quickly, so John was pulled out of Bentham Grammar School. John’s main job was as a Taker off for Bob standing. He also pugged clay and helped with the loading and unloading of the kiln. Occasionally John would do the night firing of the kiln. During the winter a kiln firing at night would attract waifs and strays from around the neighbourhood to take advantage of the “free” heat. John was always apprehensive of these vagabonds and would always make sure he had his 12 bore with him. On one occasion John fell asleep and missed charging the firemouths. When he woke up the Kiln had dropped in temperature. He spent a very worried few hours waiting to hear what his Dad would say in the morning. Fortunately the pots were not damaged due to this misdemeanour. The worst job John did was picking up wet clay from the clay pans and placing it on the clay pan wall to dry in the winter months when the clay had a layer of ice.

Stoneware bottles were the main stay of production for the purpose of spirits and Ink (Stevens Ink were a big customer). Basket casing of bottles was contracted out to William Bateson and sons now run by Gladdis Steele, Frank Bateson’s daughter. Wares similar to those made at bridge end were also produced although the difference being they were all made in Stoneware. Richard would still produce one off pots such as puzzle jugs , log like vases, he experimented combining the mill hill earthenware with the waterside stoneware to produce agate pots (these pots were fired at the bottom of the kiln as it was cooler so the earthenware wouldn’t bloat). John Bateson can recall and he still can make cuckoo whistles (I’ve seen him) from 2 pinch pots. He remembers selling these to a shop in Morecambe along with posse pots and other fancy wares.

The biggest pot made at Stockbridge was the dreaded 6-gallon bottle. This beast of a pot required a ball of clay weighing 112lbs. Just picking up a 112lb lump of clay is hard work. John can remember Richards whole arm and shoulder disappearing into the pot with the rim touching his armpit. Richard threw the whole pot in one; he used a rib on the outside and did no turning. It took two people to lift the pot of the wheel. Once made these big bottles would go into the kiln room to dry. The 6 gallon bottles were moved about by picking them up by the neck this worked fine provided there was no moisture in the clay. If the clay was still even slightly wet the unfortunate person would be left holding a bottleless neck and be in very grave danger from an irate thrower. John Bateson can remember this happening to him on a number of occasions. If nobody had seen him he would quickly wet the neck and do a quick bodge repair job so the next person to lift the bottle would get the blame. All the workers probably did this bodging until some one was caught red handed. Glazing the 6-gallon bottle was also back aching work.

An interesting aspect of this period was job experience visits by students and teachers from the royal college in London. John Bateson can recall a teacher called Miss Pinquem, who was a good sculptor. Miss Pinquem produced some 2piece moulds for the production of salt and pepper pots (in the shapes of Owls and Cockerels), and also for cuckoo whistles. These moulds where slip casted. she also worked on sprig moulds carving the blanks from plaster of Paris.

The original clay mine at Waterside had become very unstable, so a new drift mine was opened. Law required that a qualified Miner had to be employed to do this. James Singleton took this job. James had worked at Ingleton colliery. He had also spent time in the Klondike mining for gold. After going into the hill for 50 yards the mine collapsed. Fortunately nobody was down at the time. The collapse was turned into an air vent, which was just as well, as when James was working down there one time the mine collapsed badly near the entrance. James was able to escape through the air vent. The railway line from the old mine was dismantled and installed in the new mine, this meant James could transport the clay from the mine face to the Blundger with relative ease.

Business unfortunately wasn’t going very well. The war probably didn’t help this. To top it all Richard came down with pneumonia which at the time was a life threatening illness. This meant he couldn’t work for several months. Harold Parkinson in a last ditch attempt put plant in for the manufacture of sewage pipes. These machines ate the clay quicker than they could dig and process it. Worst of all after the first firing of the pipes it was very apparent that the waterside clay was the wrong mixture for pipe manufacture as the pipes buckled and warped in the kilns. This could have been rectified by additions such as grog. This would have required time and experiment. Richard would surely have sorted it out, but unfortunately he was off work ill. Specialists from Stoke could have been brought in. John Bateson thinks that at this time Harold Parkinson felt he’d thrown away enough of his money into the pottery and so declared the venture bankrupt. Stockbridge pottery ceased trading in 1944 and was the last of the Burton potteries.

Richard thankfully recovered from Pneumonia and got a job throwing with his son John taking off for him at Carders Pottery in Brockmoor in the Midlands. It was here that Richard proved his skill by being able to throw 1 gallon bottles faster than a worker (Bill Pots) could make them using a jigger jolly machine. He was however beginning to find the work harder. In 1946 Richard got a job teaching pottery at the Royal College of Art, the central school of art and Wimbledon College of art.

In the 1950s a picture of Richards hands taken by ???? Entitled “”the potters hands” won an international award and was exhibited around the world.

Richard remained in London until 1973 when he moved to Assington near Ipswich and set up a small studio Pottery, mainly for the purpose of teaching .He must have been missing Yorkshire as he moved back to within 2miles of Burton (Masongill) in 1978 and finally back to Burton itself in ????

It was during the time when Richard moved back to Burton that I first met him, although I would have only been 10 years old or so. He used to come and throw pots occasionally at my parent’s pottery (Bentham pottery). Unfortunately I was too young and also not really interested in pottery at the time. My mother though picked up a good deal of tips from him. He showed her a good method of making narrow necks in bottle shapes. My Mother has since past this knowledge on to me and I in turn have passed it on to students and other potters, so a bit of the Burton pottery legacy survives. In 1987 I wrote my thesis on the Burton potteries. This was done largely with the help of Henry Bateson (Richards’s son). I did also talk with Richard during this time, but he was an old man of 95 years by then. Richard Bateson died at the age of 98 in 1991.

When Henry Bateson tragically died earlier this year, i had the privilege of meeting John Bateson (Henrys brother). I didn’t actually realise that John had worked with his father during the Stockbridge days. This article has been produced as a result of detailed discussions with John during 2001. To the best of John’s knowledge all the details are as correct as we can get them.

Lee Cartledge July 2001.

I have uploaded an old tape of Richard Bateson talking with William Skeates about Waterside pottery here;

I have also written an account of digging the Burton Clay here.