Foreword

The following essay was produced by Hilary Bourdillon and is about her Great Uncle, the Burton-in-Lonsdale Potter Freddie Slater.

Hilary has very kindly allowed me to publish this in full on my blog, where I feel it sits well alongside my Burton Pottery related articles.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I have.

Preface

In writing this account, my intended audience is my family. I have written it to satisfy my own curiosity about the activities of my great-uncle Frederick J. Slater. I considered it important to make some sort of comprehensive record of the information I have found about him. Images therefore are for personal use and the copyright to them may be held elsewhere.

Of course, it is an incomplete and inconclusive record, and as anyone who works on the history of Burton-in-Lonsdale will know, finding the sources can be quite a challenge. The village is on the borders of Lancashire/Yorkshire and Westmorland/Cumbria, so anyone looking for information cannot always be certain where it will be found, as the cutting across administrative boundaries creates multiple locations for information. This is particularly true of incidental information such as newspaper reports. The village also shares part of its name with another pottery town, one of the much more established and documented Staffordshire pottery towns – Burton-on-Trent. Freddie Slater also shares his name with others, who at the time of writing this are on the TV and in the newspapers – namely Freddie Slater ( Bobbie Brazier) the character in East Enders and on this year’s ‘Strictly come Dancing, and Freddie Slater “one of Britain’s most exciting prospects with great success in karting as he continues to make his way up the motorsport ladder.”(2023). This can confuse and confound. I hope I have managed to avoid doing that.

Finally there is the emotional pull of researching family history – we all want our ancestors to be ‘ winners’ as programmes like ‘ Who do you think you are?’ demonstrate. What a story when it is discovered that there is Royalty in the family! I am more excited by finding trade union organisers. And that is my bias. As well as uncovering remarkable acts and astonishing achievements, family history can also uncover the unspoken and less reputable side of family activities. Those aspects of behaviour which have been swept under the carpet. In my case it is my great grandfather, William Garnett Slater, Freddie’s father, who turned into a drunkard and was violent towards his long suffering wife Alice, and in all likelihood his children too as well as other members of the village,

And so we take sides – consciously or unconsciously – and I do think Freddie is a hero who is, in need of historical rescue!

Hilary Bourdillon.

September 2023.

Searching for Freddie – The Lost Potter of Burton-in- Lonsdale.

As children, my sisters, brother and I always knew about Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries. Various items of Burton pottery graced out house. We had a money box, although we never put any money into it as we feared we would never get it out – at least not without breaking the pot. There was a rustic style pot holder in the shape of a tree trunk, a tobacco jar with a crenelated edge and other items.

We had a vague idea that one of our grandfather’s brothers had been a potter, but didn’t know anything about him, nor at the time were we particularly interested. As we played down by the river Greta we collected the pottery ‘seconds’ which we found amongst the river pebbles, rocks and hollows. Generally, we found only pottery fragments, a bottle neck here, or its base there. But sometimes we were lucky and found whole but rejected pots. The pencils on my desk are held in a misshaped earthenware small jar, possibly a mustard pot, a Burton pottery second, thrown away. In the kitchen, on top of an earthenware jar, is a wobbly, ill-fitting pottery lid, another reject, dumped on the tip by the side of the river over a century ago. Adventures by the river were escapes from visiting my father’s cousin, Harriet, who lived in Hollins house in Duke Street, and where I had to be on my best behaviour.

My father’s family lived in Burton-in-Lonsdale for years. My great, great grandfather, William Slater,(1809-1878), had been a shoe maker/cordwainer. Born in Westhouse in the parish of Thornton-in- Lonsdale in 1809. He married Jane Hoggart b.1809 from Burton-in-Lonsdale. The census returns from 1841, shows them living in Burton-in-Lonsdale. In the 1881 Census return, then at the age of 72, Jane is listed as ‘formerly schoolmistress.’

With resources like ‘Ancestry’ and ‘Find my Past’, and the www in general, it is relatively easy to find information about ancestors. Their lives are recorded in the official documents of the time such as census returns, electoral registers, the registers of Births, Deaths and Marriage etc, together with the Parish church registers. However, it is not my direct grand parents who are the focus of my interest here, but my great uncle, Freddie Slater, the potter whom we had vaguely heard about as we splashed in the river Greta.

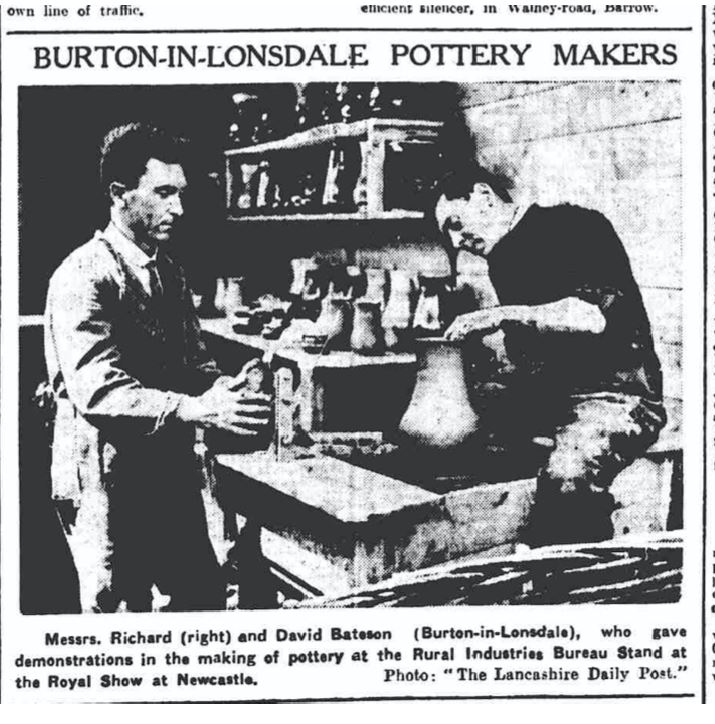

The census returns etc give information about my grandfather’s older brother Frederick James Slater. But the official records give little detail about people’s lives. At the time I began to explore my family history, Lee Cartledge’s book was published (Cartledge 2021) ‘The Last Potter of Burton-in-Lonsdale’ , which tells the story of Richard Bateson, his work as a thrower at the Burton Potteries and as a teacher at the Central School of Art in London. The book is based on the oral testimony of Richard and John Bateson. It is a history of Richard Bateson and gives a vivid account of the Burton potteries in production at the end of the nineteenth to mid twentieth century, together with information about the working lives and working conditions of some of the potters. One of those potters was my great uncle Freddie.

It is from Lee’s book, and Richard Bateson’s account, that I discovered much about Freddie, his character and his work. In brief, Freddie worked at Town End Pottery where he learnt his skill as a thrower, and his reputation as being one of the best throwers to emerge from Burton was established. In 1908 on the death of his mentor, John ‘Jacky’ Parker the owner of Town End Pottery, Freddie borrowed money to buy it. The business failed just before the outbreak of the First World War. Freddie had to find work, so he moved from Burton-in-Lonsdale to the Portobello potteries in Edinburgh, but later returned to Burton to work at Bateson’s Waterside Potteries. Lee records that it was whilst working at Portobello that Freddie:

‘discovered lots of new pottery techniques, trades unions and health and safety regulations, all of which he brought back to Burton-in-Lonsdale when he eventually returned, causing all sorts of disruption within the Burton potteries…..’(Cartledge 2021)

The ‘disruption’ Freddie caused was to form a trade union in the potteries of Burton-in-Lonsdale. He recruited members and organised a strike to ‘protest about health and safety conditions at Waterside Pottery’ (ibid 2021). Richard Bateson’s account of these events also give his view of Freddie’s character. ‘He was lord of all he surveyed.’ and he was particularly ‘Boss of all he surveyed in throwing’ ( ibid 2021). Freddie is described in Bateson’s account as a competitive, wayward character who, through his efforts to improve conditions for pottery workers, caused a great deal of disruption.

I find it fascinating that one of my ancestors campaigned for better working conditions, but Richard’s description of Freddie, his arch comments about his ownership of Town End pottery and his damning of trade union activity made me want to explore this aspect of the history of Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries in more depth. Why is the unionisation of the potters of Burton- in-Lonsdale described in the negative terms of disruptions? Why is Freddie’s organising of the union described as being a ‘bad point” outweighed by his ‘good points’ as a thrower? ( ibid. 2021) Why is this action in the potteries something not remembered in the village’s history as a moment of standing up for a better life by challenging the appalling working conditions? What is the documentary evidence for Freddie’s ownership of Town End Pottery and union activity in the potteries? Is there any evidence that gives an insight into Freddie Slater’s personality and does it paint a different picture from the challenging person who is described in Lee’s book? And why, in pamphlet after pamphlet and book after book, oral account and archive after archive, is Freddie Slater rarely mentioned? There are many potters who worked in the potteries who have not been remembered in its history. But given that Freddie was a highly skilled potter, a pottery owner and a trade union organiser, why is he only remembered in R.T.Bateson’s oral account if he was such an influential figure?

These are the questions Lee’s book raised for me, and so began my search for the potter I am calling the “Lost Potter “of Burton-in-Lonsdale, Frederick James Slater. I have searched for him in the books written about the potteries, in the archive at Lancaster University and in the Ceramic and Allied Trade Union papers at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford. In addition I have looked at the other official records in the North Yorkshire County Record Office, in newspaper reports, the census returns, trades directories, and Electoral Registers. This search has raised questions about the process of writing history and gives a clear example of how the historical record is only ever a partial and a subjective account of the past. In searching for Freddie, I hope another perspective and picture emerges to enhance and colour the history of Burton-in-Lonsdale and its potteries. This is the story of Freddie and his ownership of Town End Pottery and Pottery Trade Unions in Burton-in-Lonsdale.

Family and Early Life.

Frederick James Slater (1870-1947) did not come from a pottery owning family. He was born on 14th February 1870, the second son of William Garnett Slater who was a blacksmith in the village, and his wife Alice (née Ireland). William served his blacksmith apprenticeship in the nearby village of Wray and the 1861 census shows him aged 18, living in Wray as an apprentice to the blacksmith William Cornthwaite. The West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns tells us that William Garnett Slater (father William Slater – Shoemaker) was married in the church at Luddenden (near Halifax) on February 27th 1865. He was 21 years old. His occupation is listed as Blacksmith. He married Alice Ireland aged 23 who is recorded as being a Servant. (father Thomas Ireland – Basketmaker). Both the bride and groom were resident in Midgley at the time of marriage. This is surprising, given that fact that William worked in Wray. One possible explanation is that they were married on special licence. The likelihood is that Alice who was born in the village of Arkholme near Wray, met William, but then moved for employment to Midgley, where they were married on special licence. There is no record of where they lived after getting married. In January 1866, their first child, Freddie’s older brother, George was born and they moved back to Burton-in-Lonsdale around 1870 to open the Blacksmith’s Smithy

Alice’s family were basket weavers, which was a long established industry in Arkholme, using the willow growing by the River Lune. The 1851 census gives this entry for Alice’s family:

Thomas Ireland, 61, basket maker.

Margaret, his wife, 42.

Elizabeth, Daughter, Unmarried, Home Servant.

James, Son, Unmarried 18, basket maker.

Dorothy, 13

Jane, 11

Alice, 9

Bridget 7, and

Mary Agness 2.

By 1861, Alice was employed as a House Servant in a Henry B Denny’s household. He is unmarried, aged 49 and a farmer of 36 acres of land, living with his sister, Margaret Robinson, a widow listed as a housekeeper, and William Hutton, a widower and a Border, aged 72, listed as a Landed Proprietor.

For some reason Alice moved from Arkholme to Midgely near Halifax to work as a Servant sometime between the 1861 census and her marriage to William Garnett in 1865. Some of Alice’s relatives also moved from Arkholme to live in Burton to work as wand weavers at the potteries at around this time. The 1871 Census lists John Ireland, a basket maker (aged 62 – born in Arkholme ). He was Alice’s uncle and lived a couple of doors away from her.

The Village of Burton-in-Lonsdale 1870.

When Freddies’ parents moved to live in Burton-in-Lonsdale it had a thriving economy based on series of successful potteries, two mills ( a cotton and later silk mill and a bobbin factory ). It already had a smithy so the opening of a William Garnett’s blacksmith shop one was a sign of the increasing prosperity of the area. The village was expanding and, as demonstrated in the 1871 census returns, drew people from the surrounding area, from Ambleside, Overton, Ingleton, Sedburgh, Melling , Barbon, Rathmell, Arkholme etc. to live in the village, attracted by the employment opportunities in the potteries, the mill, the requirement for coal etc. The street where Freddie grew up was inhabited by a mixture of households which included skilled and unskilled workers. Some of the men ran their own business, and employed other men to work for them, like Freddie’s father, whilst others were in less secure occupations like unskilled agricultural labourers.

The village benefitted from the benefactions of the Thornton family. Richard Thornton (1776-1865) was born in the village. He made a fortune from the Baltic trade and was known as the Duke of Danzic’ from his strategically important commercial shipping interests during the Napoleonic wars. On his death he left an estate of £2.8 million, one of the largest ever recorded at that time. In a long list of charitable bequests, Richard left £10,000 upon trust for maintenance of schools built at my expense in Burton for poor children’. The Richard Thornton Endowed School opened in January 1854, originally intended for 46 girls and 46 boys.

Richard’s nephew, Thomas Thornton, also born in the village inherited £1 million from his uncle. Burton-in-Lonsdale’s Gothic Revival church, consecrated in 1870, was built at his expense, ‘for the benefit of his native place’. People comment on the fact that it is a large church for the size of the village, and the church in itself is further evidence of the optimism surrounding the economic growth of Burton-in-Lonsdale at the time Freddie was born. The church was designed with the expectation that the population would grow as the pottery industry and the cotton mills drew people into the village. There was also an expectation that the railway would come to Burton, bringing with it improved transport and distributions links and a consequent rise in population.

The prosperity enjoyed by Britain in the 1870’s was far from equally distributed. For families like Freddie’s living in Duke Street in 1871 life was often haphazard and precarious. Sickness and unemployment could throw families quickly into poverty and the spectre of the workhouse must have haunted most working families. For much of the nineteenth century it was illegal for working people to band together to improve their working lives and conditions. It was a criminal offence under the Master and Servant Act, which had various iterations in the 18th and 19th centuries, to abscond from employment. The servant was criminalised but not the master. There was no sick pay or old age pension, and until the 1870’s married women had no legal existence, for example they could not own property, had no rights over their children, could not divorce their husbands or of course vote in elections. At a time when women generally outlived their husbands, widowhood and old age could easily throw people on the mercy of the parish. Indeed the church records of 1873 show that the offertory for Christmas Day was ‘Given to the Poor as above – Jane Slater £2.00.’ (Vestry and Offertory. MIC 1961/0800). Jane was Freddie’s grandmother.

Frederick James Slater – Early Life

A snap shot of Freddie’s family at the time of his birth is given in the 1871 Census:

Burton-in-Lonsdale (This census does not specify the street)

William G Slater. Head. Married. 28. Master Blacksmith employing 1 man

Alice. Wife 29

George G Son 5. Scholar.

Frederick J. Son. 1

Margaret J. Daughter. 3 mths.

Freddie was baptised on January 23rd 1871. Burton-in-Lonsdale church was newly built and had only been consecrated the year before by the Bishop of Ripon. Its consecration is recorded in the Illustrated London News, May 14th 1870. The entry in the Parish Register recording Freddie’s baptism is unusual. In the margin next to Freddie’s entry is the note “Private. Received Ap 9th’. ‘Received’ refers to the ceremony when the child was publicly welcomed into the congregation. This was the convention used to note that a child had been privately baptised. Some babies were baptised at home soon after birth, especially if it was feared that they might not survive.This may have been the case with Freddie but the entry in the Parish Register appears almost a year after he was born and it is more likely to be as a result of either waiting for the new church to be consecrated, or indicative of the fact that the family did not get around to organising a christening as Alice was pregnant again with her third child shortly after Freddie was born.

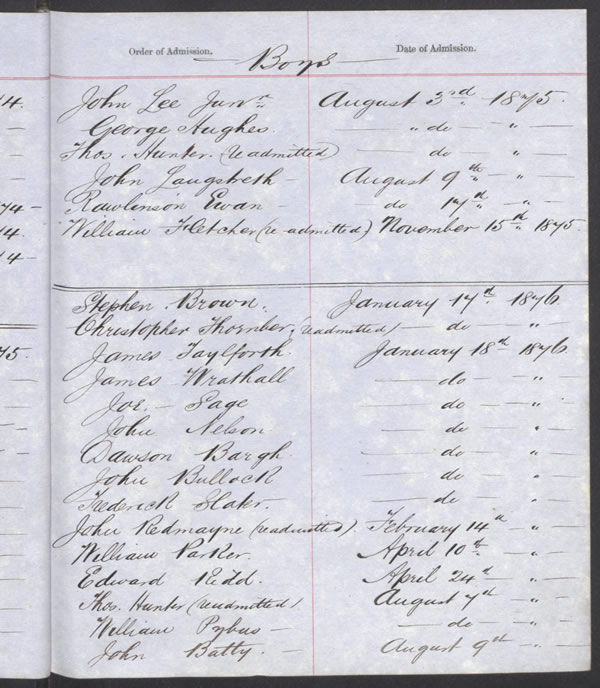

Like his siblings, Freddie went to Richard Thornton’s Endowed School.The Log book of admissions dates back to 1857, but by the time Freddie was of school age, the school was part of the National Board schools set up after the passing of the 1870 Education Act to provide a national system of education. A series of Education Acts to 1899 made education free and compulsory up to the age of 12. The National School Admission Register and Log Book for January 18th 1876 records Freddie’s admission to the school. Unfortunately, the School log book lists admissions only. There is no record of Freddie’s achievements at school.

Family Life in the Smithy.

William Garnett Slaters’ Smithy is listed, along with other tradesmen, the potters, farmers, butchers, shoe makers, publicans and shopkeepers in the Commercial section of Kelly’s Directory of the West Riding of Yorkshire, 1881 (http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk), so his business was successful and established. This success continued and business was such that William was, over time, able to apprentice three of his sons as blacksmiths to take on the Smithy. Family life in the Smithy however was far from harmonious. William Garnett was frequently hauled before the Ingleton Petit sessions. He was a drunk, quarrelsome and violent man.

Freddie’s father’s brush with the law appears to have started early as “The Lancaster Guardian” for 20th June 1857 recorded at the Hornby Petit Sessions, ” Paul Barker, George Parker and Garnett Slater, all boys under 16 years of age from Burton-in-Lonsdale were brought up for unlawfully fishing with a net in the river Cant in Tunstall and were fined, Barker 2s 6d and the others 1s each.”

Several years later, whilst serving his apprenticeship, William Garnett appears to have ‘switched sides’ and served as a Special Constable, albeit briefly. (9th May 1864 – 28 March 1865). At this time, there was a shortage of police constables and young men were encouraged to be Special Constables. Whether William joined the Specials from his own volition, or whether his master blacksmith, William Cornthwaite, encouraged him to do so, we will never know. His service record comes from The West Riding Constabulary Examination Book for 1864-67. It describes him as having brown eyes and hair and a sallow complexion, being 5’101/2” tall (The mean height, taken from military records of army recruits between the ages of 18-29, of men in the 1860’s was 5’7”). With no particular marks, the police record tells us he was born in the township of Burton-in-Lonsdale, was single and a blacksmith living in the township of Wray near Hornby, employed by William Cornthwaite. The details listed are then signed in copperplate handwriting by William Garnett Slater. He was obviously highly literate, as you might expect him to be as his mother had been a school teacher (See 1881 Census for Jane Slater).

William’s time as a Special Constable was a short-lived engagement and the record shows he left the Special Constables on 28th March 1865, possibly because he married Alice in February 1865 and moved back to Burton-in-Lonsdale to open his smithy. He continues, however, to feature in the records of the Petit Sessions.

On 12th February 1870, two days before Freddie was born, William Garnett was attending Ingleton Petit Sessions. He appears to have been involved with Francis Coates of Burton-in-Lonsdale in a skirmish with John Howson. The report of the case in the Lancaster Gazette 12th February 1870, states:

“ – Francis Coates of Burton-in-Lonsdale, charged John Howson, of the same place, with assaulting him on the 14th December last. Mr. W. Robinson, of Settle, appeared for the defendant. After a long and amusing inquiry, the defendant was fined 2s 6d. and costs. – Wm Slater, of Burton-in-Lonsdale charged John Howson of the same place, with assaulting him on 14th December last. Case dismissed.”

Three years later it is Freddie’s mother Alice, who is at the Petit Session appealing for protection from her violent husband. The Lancaster Standard and County Advertiser for 11th August 1873 records the Petit Sessions held in Ingleton:

“ WANTING HIM BOUND OVER – Mrs Slater of Burton-in-Lonsdale, asked that her husband, William Garnett Slater might be bound over to keep the peace as she was afraid to live with him, he having threatened her life on several occasions. A hot discussion arose between husband and wife and the case was adjourned for a month to see how he behaved.”

This newspaper entry is quite staggering. Not because it gives clear evidence of domestic violence, but because Alice is seeking protection from it and doing so in a very public way. At a time when married women had few legal rights, it was extremely brave act, driven by extreme desperation, to publicly ask the law for protection against a violent husband. Alice clearly led a difficult and fraught life as William Garnett’s wife. Unable to leave or divorce her husband, her life with William Garnett was one of constant child bearing. William and Alice had eight children, six boys and two girls between 1866 and 1886, one of whom was my grandfather William Henry Garnett Slater.(1877 – 1960). Worn down by her constant childbearing and in fear of her life she must have had great determination and resolve in order to survive.

So it seems that Freddie’s early life was surrounded by domestic abuse, drunken violence, and disputes with neighbours. Several years later, when Freddie was 8 years old, his father was involved in another case with John Howson, this time at Kirkby Lonsdale County Court. The Lancaster Gazette, 16th February 1878, reports:

“ SLATER Vs HOWSON – Mr. Tilly appeared for the defendant and Mr. Picard for the plaintiff. – This was an action brought by William Garnett Slater, blacksmith, of Burton-in-Lonsdale, against John and Anthony Howson, of the same place, for the payment of £12 4s. 4d. owing, the balance of account for work done and materials supplied. Defendant’s father died four or five years ago and they succeeded to and carried on the business, but when the plaintiff sent in the bill they denied they were in partnership – Evidence in support of the partnership having been given, his Honour adjourned the case in order that Anthony Howson, who had left the neighbourhood, might be found and summoned to attend.”

Quite what the outcome of this case was is unknown. What’s more, William Garnett’s court appearances did not end there. In the 1890’s, he appears in the Ingleton Petit Session again. This time, not as a defendant, but charged with being drunk and disorderly. The Lancaster Standard and County Advertiser, 12th May, 1893, reports this:

“ DRUNK and DISORDERLY – ………William Garnett Slater, who is an old offender, was again charged with being drunk and disorderly at Burton-in-Lonsdale, on 11th April – PC Steel said he saw the defendant, who was very drunk, cursing and swearing in the street. He asked the defendant to go away, but he continued very noisy.-Supt. Gunn, in answer to the Bench, said defendant was also before them in July last – Fined 10s. and costs.”

The reputation of his father seems to have rubbed off on Freddie. P.C.Steel, who lived around the corner from the Smithy in Low Street, Burton-in-Lonsdale, may well have had his eye on the Slater family, and when he caught Freddie riding his bicycle without lights in May 1890, he decided to make him an example to others.

“Lancaster Guardian of May 10th, 1890,

A Warning to Bicyclists

Frederick James Slater, Burton-in-Lonsdale was charged with riding his bicycle without a lighted lamp, on the highway, at Burton, and pleaded guilty. P.C. Steel stated the case – Fined 2s 6d without costs.”

£1 in 1890 is worth around £125 today.

These court appearances demonstrate that life in the Smithy was full of tensions and violence. In a village the size of Burton-in-Lonsdale it would be easy for families to get the label of being ‘difficult’, and for the reputation of fathers to rub off on their children. The prevailing order meant that people were highly aware of social status. Court appearances, reported in the local press, would no doubt be the subject of gossip in the village and count against a family. Gossip was a mechanism of social control to ensure that the prevailing mores were not challenged. At a time when there was no radio, television or cinemas, no soap operas and scandals amongst so-called ‘ celebrities’, villagers constructed their own dramas from the lives of those around them. Reputations were remembered by those who wanted to see themselves as being socially superior. It seems Freddie may well have been tarred with the brush of being troublesome from the start, because of his father’s reputation for violence and drunkenness. The razor thin divides in social status may well explain Richard Bateson’s view of Freddie as being ‘ a strong and unwieldy character’.(Cartledge, 2021) ‘ fiercely competitive’, and he ‘always wanted to be in front of other throwers in terms of throwing speed and volumes of pots made’ (ibid ). Richard Bateson was clearly in competition with Freddie Slater as to who was the best thrower, ( Cartledge 2021) but Richard was convinced he was Freddie’s social superior, hence his negative descriptions of him in his oral account of the potteries.

Into the Twentieth Century

The Census for 1891 shows Freddie, aged 21, was still living in the family home with his parents, brothers and sister.

The 1891 Census

William G Slater.Married. Head 47 Blacksmith

Alice. Wife Married 48.

George G Son Single 25 Blacksmith

Frederick J. Son Single 21 Pot manufacturer.

Arthur. Son. Single 18 Blacksmith’s Apprentice.

Ada. Daughter. 16 Dressmaker’s Apprentice.

William Hy Garnett Son 14

Albert G Son 5.

The Smithy was prosperous enough to employ George and Arthur. Later, William Henry Garnett Slater also trained and worked as a blacksmith. But Frederick became a potter rather than a blacksmith. Maybe Freddie did not want to work with his violent and drunken father. Maybe it was his links with the Irelands who came from his mother’s village of Arkholme and who worked as basket makers at the pottery which familiarised him with the work. Whatever the reason, was throwing pots at which he shone, rather than forging horseshoes.

Freddie’s older brother George Greenwood inherited the forge on the death of his father in 1897. As George’s own family grew, and as the demands for blacksmithing changed, the Smithy would no longer support everyone in the family, particularly as they themselves got married and had children. By 1901, the family was too large and employment prospects were changing to allow everyone to continue living in the same household. Far from attracting people from the surrounding villages to Burton-in-Lonsdale for work, conditions were such that people began to drift to the Lancashire cotton mills for employment. But Freddie (now aged 31) was still living there, presumably because he was bringing in an income. He did not leave the family home until after he married.

All this may seem irrelevant to Freddie’s work as a potter, a pottery owner and a strike organiser, but it serves to demonstrate just how fragile many people’s livings were at this time. It was easy to slip into poverty and destitution, and this possibly explains why Freddie developed the attitude that he had to support his family at all costs and search for any opportunity to do so – like going to Portobello when his own business failed and looking for opportunities to supplement his income through taking on paid jobs for the Parish. (see below). There was no cushion of family wealth to break Freddie’s fall if he fell. It is also important to establish Freddie’s background in terms of explaining his character and to explain what influenced other people’s views of him. The social hierarchy of villages, like other rural communities at that time, where it was easy for the label ‘troublemaker’ to stick, was deeply imbued with a culture of doffing the cap: people were expected to know their place, not challenge the social conventions and certainly not belong to Trades Unions. So it demonstrates Freddie’s strength of character that he did just that.

Freddie got married in 1905, aged 35. His wife, Margaret Grace (née Fletcher) was nine years his junior and the daughter of a bricklayer’s labourer. She had lived round the corner from Freddie in the High Street. For the first two years or so of their married life it seems likely that Freddie and Margaret lived either with Freddie’s family or with Margaret’s, as Freddie does not appear in the Electoral Rolls for Burton-in-Lonsdale until 1907.

Freddie’s eligibility to vote is important in his story since the Electoral Registers tell us where he lived. The West Yorkshire Electoral Register for 1907 shows him living in High Street Burton-in-Lonsdale. My attempts to find other documentary evidence of Freddie as a pottery owner and trade union organiser sent me down many roads which initially led only to the Batesons and R.T. Bateson’s account of the Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries. Why that is so is answered by looking at how the histories of Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries have been written.

Looking for Freddie the Potter : How History is Hidden.

At first glance it would appear that finding out about Freddie’s ownership of Town End Potteries would be an easy task. There are several books published on Yorkshire pottery and Burton-in-Lonsdale pottery in particular. There have been special exhibitions on the subject and then there is the Stan Lawrence Archive held by Lancaster University. So it was extremely disappointing to find that not a single one of these sources mentions Freddie as the owner of Town End Pottery or as a union organiser.

i. The Stan Lawrence Archive.

I approached the Stan Lawrence Archive at Lancaster University with great anticipation, thinking I would find some original and as yet unpublished material and a new story about the potteries. The archive is a fascinating collection of documents on the history of many aspects of Burton-in-Lonsdale, not just the pottery industry, collected together by Stan Lawrence (1926-2013) who was the Headteacher at Burton-in-Lonsdale Endowed Primary School until 1986. The archive index is full of promise (See Appendix for the index of pottery references). Initially excited and hopeful of finding out about the Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries and Freddie Slater, my search quickly became a trawl through familiar documents. They all tell much the same story, the story of the Bateson Family and their ownership of Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries, much of which is covered in Lee’s book. There is an oral history with Stan Lawrence interviewing Richard Bateson, together with another oral account where Richard Bateson reminisces with the pottery worker- Jimmy Skeates. (Search YouTube – Burton-in-Lonsdale Potters). All the photographs of the potteries to be found in the Stan Lawrence Archive are the same as the ones found in all the histories of Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries recently published. These come from some photographs Richard’s daughter, Margaret McKergrow, took to use up a roll of film. They show Waterside/Stockbridge Pottery around 1940. (Cartledge 2021. Acknowledgements)

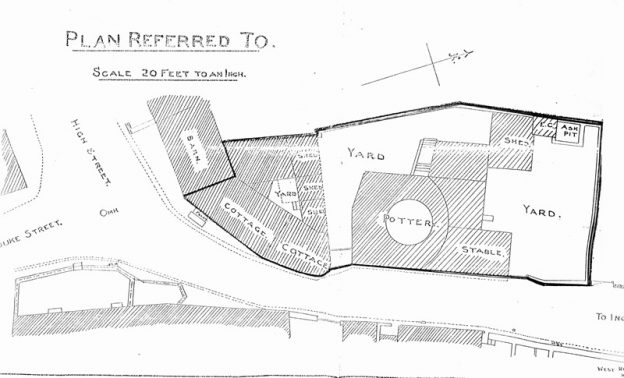

The gifting of this archive to Lancaster University by Stan Lawrence means that Richard’s account of the potteries is preserved and accessible. As a result it has come to dominate the story of Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries and has become the much quoted narrative about the life and conditions in the potteries, obscuring any others. Anyone consulting the archive at Lancaster University for information about the potteries at Burton-in-Lonsdale will find nothing about trade union action in the potteries and so will be given only one part of the picture. For example, this is the section on Town End Pottery in the archive:

SLA/1/4/Town End

Town End Pottery- Stan Lawrence’s deeds notes. found in SLA/1/2 – History ofBIL.

Sub-fonds = SLA. Series = Autograph Typescript and Manuscript. File = Notes File. Item= History ofBIL Item.

This document indicates that Town End pottery, originally owned by Thomas Bateson (1740-1806), passed though various members of the Bateson family until James Wilcock Bateson ( b. 1846 ), who married Rebecca Bradshaw (another Burton pottery family) from Bridge End Pottery, in 1869. They gave up potting and left Burton around 1872.

There is little information on the subsequent owner of Town End pottery – Jackie Parker – and nothing about Freddie’s ownership and the demise of Town End pottery.

Undoubtedly, Richard was highly successful and accomplished and is to be much admired for his work both at and about the Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries. His family had been pottery owners for many years and his is an important history, but maybe there are other interpretations. The historical account is inevitably determined by those who leave a record, whilst the lives of others, are side-lined and forgotten. This is not necessarily done deliberately, but happens through the particular process whereby some accounts of the past survive, and others are hidden from history.

ii. Published works and recent exhibitions.

Freddie’s ownership of Town End potteries does not feature in any of the published works about Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries either, apart from Cartledge’s book. This in itself raises questions about the process of history and how history is written.

A succinct account of the Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries is given in Oxley Grabham’s “ Yorkshire Potteries, Pots and Potters.” (1916) and this publication seems to form the basis of most secondary sources until the recent publication of Lee’s book.

See – https://archive.org/details/yorkshirepotteri00grab/page/10/mode/2up

Grabham has a section on each of the five Burton potteries in production at the turn of the century. The short paragraphs on each pottery summarise origin and ownership, saying nothing about methods of production or how the potters worked. This is his entry for Town End Pottery.

“ Town End Pottery manufacturing back and brown ware etc. was worked by Thomas Bateson in the early part of the 18th Century, and some think there was a Gibson before him. Thomas Bateson was succeeded by John Bateson, and he in turn by another Thomas Bateson. The last of the four generations was Richard Bateson. This terminates the Batesons at Townend (sic) Pottery about 1853, when William Parker took up the business and it is now worked by his brother, John Parker.” ( ibid )

Grabham attributes his information about the Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries to the owner of Baggaley Pottery, Mr Thomas Coates “who most kindly supplied me with much information about these potteries.’ (ibid).

However, the entry for Town End Pottery is obviously inaccurate. John ‘Jacky’ Parker had died in 1908 (Cartledge 2021), so he was clearly not running the business in 1916. To give Grabham his due, he did at least seek information from Thomas Coates who knew the Burton Potteries, but he obviously collected his information several years before his book was published – hence the inaccuracy. By 1916, the date Grabham’s book was published, Town End Pottery, having been bought by Freddie Slater on Jacky Parker’s death, went out of business round about the outbreak of the First World War.

It seems Grabham’s account is the basis for other accounts of the potteries. It is his work which informed the article ‘The Potters and Basketmakers of Burton’ by James Walton in his article for The Yorkshire Dalesman. (1930-1940). Other accounts of the Burton in-Lonsdale potteries are, Brears, P .C.D., The English Country Pottery , (Newton Abbot, David & Charles I971) and Lawrence, H., Yorkshire Pots and Potteries, (Newton Abbot, David & Charles 1974). These document the history and products of the Yorkshire potteries from medieval times to the twentieth century. Lawrence’s book deals in more detail with Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries than Brears’, but both books appear to rely very much on the Bateson and Grabham sources. Lawrence states that Town End went out of business sometime early in the 20th century. There is no mention of the unionisation of potters or of the working conditions for the pottery workers in either book and the short articles and exhibition leaflets focus on the pots rather than the potters.

There is also a series of booklets which look at the Burton Potteries, for example Prospects, ‘Lonsdale Potters Then and Now’, (Prospects, November 1965 University of Lancaster Bulletin of the Month’s Events), White, Andrew, ‘Country Pottery from Burton-in-Lonsdale’, Local Studies, No. 10, (Lancaster City Museums, 1989). and Lancaster City Museum, Burton-in-Lonsdale Pottery, Jan/Feb 1987. Exhibition. These are leaflets for exhibitions, and they again focus on the pots rather than the potteries or the potters. Dating from the 1980’s one might have expected these publications to give at least some emphasis to the potters who made the pots and their organisations since this had been the focus of the wider historical scholarship and the history research community since the 1970s, typified by publications such a The History Workshop Journal. These exhibition publications were untouched by this new scholarship which embraced ‘history from below’ giving emphasis to the people who worked in these industries and their trades unions.

Historians do not always go back to the original sources in their exploration of subjects, but frequently rely on secondary sources written by other historians. In this way, myths and omissions are perpetuated. So Freddie and the later history of Town End Pottery has been written out of these history books, as indeed has the story of people like Thomas Coates, the owner of Baggely Pottery and his support for the campaign to persuade the Midland Railway to build a station at Low Bentham, thus making the railway more easily accessible to the Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries and make distribution and sales more economical and practical.

The dominant voices in the secondary sources are those of pottery historians, who are interested in pots and techniques, or of the pottery owners. The pottery workers themselves were not given a voice. One account which does mention Trade Unions does so negatively. In 1949, an article in ‘The Dalesman’ for March 1949 by Eric and Bessie Tapsell, include this comment :

“‘ Preserve us from Trade Unionism and internal broils.’ was the prayer of master potter James Bateson, an honest, godly man and a local preacher, still remembered.” ( Dalesman 1949 pp 452-455)

This implies that because he was an honest and godly man, James Bateson’s view must be correct. No explanation is given as to why this comment was made in the article, but it may well be linked to the pottery strikes in Burton-in-Lonsdale. It wasn’t only amongst the pottery workers that trades unionism began to take a hold, but also amongst the miners in Ingleton, the railway workers, the joiners and Master Carpenters in Lancaster etc (See, for example, the report in The Lancaster Gazette . Wednesday Sept. 7th 1892)

Disappointingly, more recent work on the Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries, ignore the unionisation of the pottery workers. An exhibition focussing on the Burton Potteries was organised at the Museum of North Craven Life in 2015. “A Community Skill: the Story of Burton-in-Lonsdale’s Potteries Museum of North Craven Life, The Folly, Settle, Exhibition 2015: panels“ ( see http://www.ncbpt.org.uk/folly/exhibitions/exhibitions_2015/panels/burton_potteries_panels.pdf) This shows many aspects of the everyday lives of the potters, but it does not mention any trade union or collective activity amongst the Burton pottery workers to improve pay and conditions. It does, however, have a section on working conditions:

“Working Conditions

The potters in Burton worked in difficult conditions. Their jobs were often dangerous.

The atmosphere in the potteries was often very uncomfortable. When the kilns were firing, the whole pottery would be extremely hot and smoky. The kilns were unpacked whilst they were still very hot. Workers could only bear to be at the top of the kiln for a couple of minutes at a time. Kiln packers also breathed in large amounts of flint dust. This caused silicosis which could be fatal.

There were other hazards too. The materials used in glazes were often poisonous and handled without protection. Arthritis was common amongst throwers. Some workers did escape unscathed though. Richard Bateson worked in the potteries from the age of 13 and lived to be 98.” (http://www.ncbpt.org.uk/folly/exhibitions/exhibitions_2015/panels/burton_potteries_panels.pdf)

This coverage of working conditions is apologetic to say the least. The fact that Richard was lucky enough to live until he was 98, and the fact that he worked in the same conditions as his employees, does not remove the dangers to health of working in the potteries. Nor does it compensate for the early deaths of many of the pottery workers. It is a complete misrepresentation of the past to minimise the appalling conditions in the potteries. Harry Bateson, Richard’s father died at the age of 66. “ He was the centre of the machine, sitting the pottery wheel throne creating the very rhythm of the work amongst all the filth clay and dust.”( Cartledge, 2021). Richard’s brother, Peter died of silicosis. “ Richard could reel off a list of the men who had died of silicosis at Waterside Pottery.” (Cartledge, 2021).

Apart from silicosis, there was the danger of lead poisoning, and this was a particular hazard at Town End Pottery and one which possibly contributed to Jacky Parker’s death in 1908. Red lead glaze was used on the pots at Town End pottery. Lead was relatively cheap, gave a hard shiny finish after firing and could tolerate a wide range of temperatures. It is absorbed through the skin, by inhalation, or through the mouth. It tended to be absorbed into the bones and affected the tendons. This caused “dropped wrist” and “dropped ankle”. Other symptoms of lead absorption included stomach disorders,, anaemia, epilepsy and paralysis. Many workers died of lead poisoning (plumbism). Alternatives to the use of lead were expensive. In the main pottery area of Stoke-on-Trent, the pottery owners attempted to blame the early deaths amongst their workers on “the slovenly habits of their employees!”. (Goodby 2022). After 1896 it became a requirement to report deaths from lead poisoning. They were found to be 50% higher amongst potters than in any other industry. A Government enquiry into lead poisoning in 1898 resulted in the banning of the use of raw lead. After 1st January 1899 all workshops had to be ventilated and cleaned at the end of the day. It was decreed that no more than 5% standard solubility of lead would be allowed in glazes and a detailed set of rules was drawn up, which restricted the use of lead. After this date lead poisoning in workers began to decline (https://www.search.staffspasttrack.org.uk/). Employers were also requested to provide protective clothing and washing facilities for their workers. I can see no evidence of protective clothing being worn in the photographs of the Burton-in-Lonsdale pottery workers. I don’t think they have changed for the photographer.

So it was in the interests of the pottery owners to minimise and suppress any ideas that working in the potteries was a danger to health, and to oppose any attempt by the workmen themselves to improve conditions. They did not want to have the additional expenditure of providing washing facilities, protective clothing, or payment for cleaning the premises at the end of every day. Hence the dismissive comments about trades unions and Freddie’s involvement in them, in the Bateson narrative of Burton-in-Lonsdale’s potteries.

Fortunately, my search did turn up some evidence, ignored by all these histories, which consider Freddie the pottery owner, and trades union action in the Burton potteries.

Part 2.

Freddie – Pottery Owner. 1908-1914.

There is clear evidence of Freddie’s ownership of Town End beyond the oral

account of Richard Bateson. In the Electoral Register for 1908, Freddie was

still living in the High Street. That is the year Jacky Parker died, and in the

following year 1909, Freddie was listed as living at Town End Pottery and was

qualified for the franchise by two properties – a house in the High Street and

Town End Potteries. The 1910-14 Electoral Register has him living at Town

End Potteries Burton-in-Lonsdale, Dwelling House (UK, City and County

Directories 1600-1900s) , as do the 1 entries for 1918-23.

The 1911 Census likewise gives evidence of Freddie’s ownership of the

pottery. It shows Frederick James Slater, aged 41, Pot Maker, Manufacturer,

and listed as an Employer. Living with him are his wife, Margaret Grace, 32,

and two daughters, Edna, aged 5 and Alberta, aged 1. Further, the entry in

the Trade Directory for 1913 for Burton-in-Lonsdale has the following entry:

‘Slater, Fredk. James, manfctr. of brown ware pottery, Townend Pottery.’ (UK,

City and County Directories, 1766-1946)

Apparently Freddie failed as a pottery manufacturer because he was ‘too

busy advising other people how to run their business, instead of running his

own’ ( Richard Bateson quoted in Cartledge 2021). According to Richard

Bateson’s account, Town End pottery failed because of the Freddie Slater’s

character. There is however, another interpretation of Freddie’s motives to

raise a loan and buy Town End Pottery. The pottery had to continue in

production in order to protect livelihoods and income. Jacky’s son, Jim, had

no interest in the pottery and although Jacky had daughters, women potters

were unheard of in Burton-in-Lonsdale at this time, (Cartledge 2021). So what

was to happen to the pottery? It could well have closed down in 1908 with the

resultant loss of jobs, including Freddie’s. In the 1913 Trades Directory,

James Parker (the Jim who was not interested in taking over the pottery) from

Stone Bower Cottage is listed as a ‘Worker at Pottery,’ so Freddie’s

purchase of the pottery enabled Jim to earn a living without the responsibility

and debt of ownership. Given Jim’s lack of interest in owning the pottery,

Freddie may well have decided he had no option but to buy it in order to

protect his own and other working mens’ livelihoods.

Freddie’s ownership was short lived. He clearly did not have the advantages

of having inherited a pottery like the Batesons. Freddie ran the pottery for

around five or six years and then as Britain went to war with Germany in 1914

he had to give it up.

The Trades Directory for 1913 for Burton-in-Lonsdale which lists Freddie as a

Pottery Manufacturer shows how challenging it was to make a living at that

time. ‘Multi-occupation’ seems to have been the only way to provide

economic security for many families in Burton-in-Lonsdale. The Trades

Directory lists Thomas Coates, flower pot and earthenware manufacturer, but

he is also as an overseer and victualler at the Punch Bowl. Likewise, Mrs Eliz

Brayshaw ran a lodging house in Duke Street and worked as the school

caretaker, Charles Arthur Brownsord was a victualler, butcher and ran the

‘Hen and Chickens’. John Alphonso Harrison was a tailor and outfitter,

stationer and postmaster, George Edward Maud was a farmer, caretaker and

ran the ‘pleasure gardens, Alexandra Hall’, William Tatham was a grocer, cab

proprietor, coal merchant and farmer at Burton Houses. Freddie had only one

income coming into his household at this time as well as paying off his loan,

so maybe the odds were stacked against him.

Lee Cartledge has provided me with this analysis of the failure of Town End

Pottery:

“Prior to the First World War, the Burton potteries were experiencing

something of a boom, so it may seem surprising that Town End pottery under

Freddy Slater went bankrupt. The stoneware bottle manufacturers in Burton

were doing particularly well around this time (Waterside Pottery, Coates/

Baggaley Pottery). Town End pottery though was an earthenware/ country

pottery manufacturer and I suspect the demand for these traditional pots was

waning, due to increased availability and competition from enamel ware and

pottery from Stoke.

The question is why didn’t Freddy move into the more lucrative

stoneware bottle manufacture? There are really two reasons why I

suspect he didn’t:

o The Town End pottery kiln would have only been designed for

firing up to 1100 degrees. It would have had to have been rebuilt to

achieve the 1300 degrees required to fire pots to Stoneware

temperatures. It would have had to have been converted from a through

draft kiln to a down draft kiln. This would have cost a lot and would have

inevitably have caused down time.

o Possibly the main reason though is Freddy had no access to

any Stoneware clay at Town End Pottery. The earthenware clay was

accessible open cast on common land (Mill Hill) and all people in the

parish of Burton and Low Bentham have a right to dig it (even today).

The Stoneware clay though was on private land so he would have had

to negotiate and pay to dig it. It wouldn’t have been in the Coates or

Batesons’ interest for Freddy to share their stoneware clay sources.

In truth a lot of the traditional country Potteries began to experience

difficulties around this time and many were forced to close down in the

years after the First World War. That said, there are examples of some

that survived through this period, e.g. Wetheriggs, Oswaldtwistle Pottery,

Soil Hill Pottery and Pearsons of Chesterfield.

In all likelihood I suspect that Freddy may have borrowed too much

money at a time when earning a living from traditional hand thrown

pottery was becoming increasingly challenging. R T Bateson always

said that it took a minimum of eight men and one horse to run a Burton

Pottery, which is a lot of wages (and hay) to pay out! Had Freddy

inherited the pottery then I’m sure it would have been a different story.”

( Email 11/03/32 Lee Cartledge)

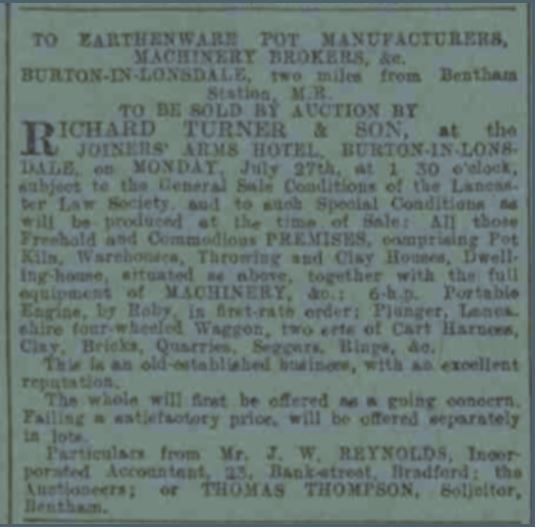

This advert was placed in the Lancashire Evening Post on 21st and 22nd July

1914.

It is unclear if this is a notice of sale for Town End potteries, but it is likely to

be so. Richard Turner & Sons unfortunately have no records of their sales

going back this far, so they have been unable to provide me with any further

detail about the sale. How much of it was sold is unknown.

To Portobello.

(Historic Scotland – photo from display board at the Portobello kiln.)

Having failed to keep Town End Pottery going, Freddie had to find work to

support his family, so around the end of 1914, “ Freddie then moved out of

Burton and got a job at Portobello Factory Edinburgh. His family stayed in

Burton which probably explains why he moved back to Burton as soon as he

could.” (Cartledge 2021) This would have been an extremely difficult time for

Freddie leaving behind his family. His older brother, George, who was

successfully running the Smithy and training his sons as apprentices, died in

1913 at the age of 47, leaving a young family.

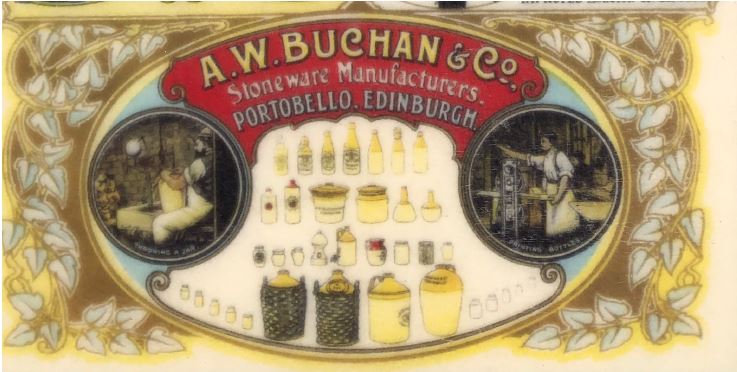

The pottery in Portobello placed this advert from the ‘Staffordshire Sentinel,’

Tuesday, April 7th 1914:

“Stoneware Turners ( two) wanted at once for Jam Jars, Creamers etc steady

employment. W.A.Gray & Sons Midlothian Potteries Portobello, near

Edinburgh.”

Although a less skilled job than a thrower’s, this advert shows the potteries in

Portobello were looking for workers as the war recruitment drew men to the

Western Front. The timing of this advert would fit with Freddie looking for

work. It is likely he worked at the Buchan pottery which produced stoneware

at this time. ( See advert Fig. 4 above)

Where he lived in Portobello and what exactly he did, I have no record, but

“Freddie brought back some of the new techniques he’d learnt in Edinburgh

back to Burton…….. he also introduced trade unions to Waterside

Potteries.” (Cartledge 2021.) It is difficult to establish how long Freddie

worked in Portobello. What is certain is that Freddie would have come across

Trade Unions in Portobello – the trade union movement being strong in the

Scottish Potteries.

Pottery Unions.

Searching the records of the National Society of Male and Female Pottery

Workers (See WCML papers), I have been unable to trace individual

memberships. Nor is there any evidence of a Union Lodge at Burton-in-

Lonsdale, it being far too small a workforce compared with Hanley, Stoke,

viii

Longton, Fenton, Newcastle N, Newcastle S, Swadlingcote, Portobello etc

etc. These are some of the Trade Union Lodges for the National Society of

Male and Female Pottery Workers in 1915. This is the Union Freddie was

likely to have encountered in Portobello. The Union was formed as a result of

the merging of several pottery unions. In 1908, the Associated Stoneware

Throwers, Bristol Stone Potters and the Society of Operatives and Engravers

joined the Union. It eventually changed its name to the National Society of

Pottery Workers in 1919.

Freddie’s move to Portobello coincided with a period of great national

industrial unrest. Britain’s economic output had been overtaken by the USA

and Germany. According to the 1911 Census analysis, the richest 1% of the

population held around 70% of the UK’s wealth. Real wages dropped by 10%

between 1900 and 1910 whilst food prices went up. So this period saw the

steady economic decline of the UK on the world stage; the growing division of

wealth; the steady fall in the real value of wages and the growth of trade

unionism and trade union membership as well as militancy. By 1906 there

were just over 2 million trade unionists and by 1914 the number was over 4

million, or 27% of industrial workers. According to the Office of National

Statistics, 18 millions days were lost through strike action between

1910-1913, rising to 5 million in the first six months of 1914.( https://

www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/

employmentandemployeetypes/articles/thehistoryofstrikesintheuk/

2015-09-21) This shows the level of frustration and unrest among workers

who attempted to improve wages and working conditions. The action was

reduced only by the advent of the World War.

It appears that the Pottery owners in Scotland at this time decided to launch a

united front against demands from the pottery unions and control pottery

workers’ wages, working conditions and working hours. On 16th January

1914, Members of the The Potters Federation LTD.,which included the

Portobello potteries of Portobello Pottery and A.W.Buchan & Co submitted a

claim for ‘The alteration of Wages and conditions of Employment’. ( TU/

CERAMIC/6/5 WCML)

This claim proposed “Reducing the Throwers General Price List by 12%”

resulting in “ a reduction in the time rate of wages to 35/- per week of 60

hours.” This, claimed the pottery owners, was justified by the fact that the

thrower no longer had to pay his ‘second hand’ ( who turned the wheel)

because the wheel was no longer driven by hand; and:

“ The employers make this claim most unwillingly, but think it is in the interest of

the Stoneware trade that these reductions be made so that workers may in future

have work to do, and that employers have more work produced per worker

employed.”( TU/CERAMIC/1 1911-1998 WCML )

This document shows that pottery throwers in 1914 could earn far more than

skilled workers in a cotton factory. Nevertheless their income was being

eroded like all workers’ incomes at this time. The claim to reduce throwers’

wages was strongly resisted and the Secretary of the Potters Federation,

Robert Bird, who had filed the above petition on behalf of the pottery owners,

had to appeal to the General Secretary of the National Society of Male and

Female Pottery Workers, Joseph Lovatt, to encourage its members to go

back to work with this telegram:

“ Grosvenor says Kilnmen still out. Works stopped. Please write them to go in or

trouble may spread.” (ibid WCML) etc etc.

Amongst the Union papers there are letters and telegrams between the

Scottish pottery owners and Joseph Lovatt over working conditions,

threatened strikes, appeals to encourage the men back to work, details of

arbitration etc. It could be argued that the Union was as much an instrument

of control as much as a militant force, particularly as the war progressed and

men signed up to fight. Skilled workers were harder to come by and the

shortage of labour meant the men had increased leverage. The Union was

called in to get the men back to work. This letter is from the Midlothian

Potteries, W.A.Grey & Sons, Manufacturer of All Kinds of Stoneware etc.

Portobello. It would have been written around about the time Freddie was

starting work at one of the Portobello potteries.

“ 10th August 1915

Mr. Jas. Lovatt,

Secretary, Amalgamated Society of Pottery Workers,

Hanley.

Dear Sir,

We regret to say Wm. Railly who was with us as a Thrower before the

Strike, has not returned up and he has been taken on by Mr. Kennedy’s foreman

under a misapprehension.

We have only four Throwers left- some having enlisted, sometime ago and we

are really requiring Railly and as it is part of the bargain that the men return to

their work “ as they were” we shall be glad you will kindly instruct him to come

back to his post here, Mr. Jas Kennedy is quite agreeable to this and in fact would

not have given him a start had he known the circumstances……”

( TU/Ceramic/ 1 WCML)

There was strong union organisation across the pottery industry in Scotland,

so it is not surprising that Freddie Slater, working in the Potteries in

Portobello, became involved in their activities, and began to appreciate the

strength of collective action.

That’s not how we do things here – Rural hegemony and anti

union sentiment.

The story seems to have been very different for the potteries of Burton-in-

Lonsdale, where Trades Unions were slow to develop. The Burton potteries

were small compared with the huge pottery complexes in Staffordshire and

Scotland The pottery workers knew the pottery owners. They worked

alongside them and they often had other roles in the village. For example,

Thomas Coates ran the Punch Bowl as well as Coates Pottery, the Batesons

were members of the Parish Council. Harry Bateson was a church warden,

and so on. The pottery owners are in evidence at village events like the

annual Burton-in-Lonsdale show and were rivals with their employees for the

top prizes. There was not the clear divide between owner and employee like

that found in the larger potteries of Staffordshire and other places.

Trade Unions were affiliated with the emerging Independent Labour Party

(ILP) and their stronghold was in the large urban factory complexes in

Scotland, Lancashire, the coal mines of Yorkshire and Northumberland etc.

The two developed in tandem. The Lonsdale area was always staunchly

Liberal or Tory in its Parliamentary vote, and the interests of the landed gentry

dominated and led the political persuasion of their employees. There is little

evidence of the growth of the Independent Labour Party, and the affiliated

Trades Unions in this area at the beginning of the twentieth century. This one

article indicates the ILP did have some presence:

“ Bentham ILP held a very successful meeting at Burton-in-Lonsdale on Monday

night, when the Rev. B. Proudfoot, of Halton, lectured on “The Need and Justice of

Socialism.” The lecture was greatly appreciated, and the Vicar, The Rev. Thomas

Leach presided and let us (sic) the church Sunday school free of charge. This is the

first I.L.P. meeting held in the village and the room was filled. ……..”

(‘Labour Leader’ 18 Oct. 1907)

Who filled the Sunday school room for the meeting is not recorded.

Unlike the large industrial complexes of the nineteenth and early twentieth

century towns and cities, Burton was a rural pottery and the patronage of

church and landed gentry was still an important factor in the economy of the

local families. Freddie himself supplemented his income, participating in the

Parish Council meetings and being given paid work for carrying out some of

their responsibilities, for example :

In Burton-in-Lonsdale, the Parish Council minutes for 1910 notes:

“ Tuesday, 29 March 1910

F.J.Slater oil 10s 0d.

J. Parker “ 8s. 0d.

F. Slater “ 19s.9d.”

Presumably Freddie was supplying oil for the street lighting in Burton-in-

Lonsdale. In 1894, under the Local Government Act, parish electors could

agree, following a poll, to adopt the Lighting and Watching Act, first passed inThe “Lighting and Watching” Act of 1833 allowed groups of property

owners to form committees and organise local street lighting. It also allowed

for the creation of local police forces – the “watching” part of the Act’s title.

These committees were then empowered to levy a rate on other

householders to pay for the lighting (or policemen).

The payment to Freddie for oil also explains why he supported the Lighting

and Watching Act viz:

“ 28 October 1911

Prop. F. Slater, Sec. J. Dickinson that the Lighting Act be adopted.

£17 for Lighting and Watching Act.”

( SLA/11/1 BIL Council. Minutes of Burton-in-Lonsdale Parish Council,

1895-1923.

Sub-fonds = SLA. Series = Minute Books. File= Corporation File)

The church was another provider of employment, and although it might

appear that the Rev Thomas Leach may have had some sympathy with

Socialism, it wouldn’t be politic to upset the Vestry lest the work they paid for

ceased. The Slaters received payment from the church for repairs. Cleaning

the church provided a regular, if meagre income, £1. 3s. 6d. for one of the

Mrs. Slaters (North Yorkshire County Record Office. 1631-1998 records. PR/

BTL). So to rock the boat, to question the established order and the way of

working may have had serious economic consequences through the

withdrawal of patronage in this community.

Potters would often work on local farms at hay time to supplement their

income.(Cartledge 2021 p.24-photo of Potters hay timing in 1910). This

interdependency of pottery owners and employees for work and livelihood

meant that any criticism of them was suppressed and anyone who did raise

objections to the length of working hours, the rates of pay, or the working

conditions, as in the case of Freddie Slater, was labelled a ‘troublemaker”.

Lee acknowledges that forming a union at Waterside Potteries ‘ has to be

seen as a brave move on Freddie’s part.” (Cartledge 2021 ibid)

Back in Burton-in-Lonsdale.

Freddie did not stay long in Portobello – but without the evidence from

Electoral Rolls it is difficult to say how long. He moved back to his family,

continued to live at Town End Pottery, and found employment at Bateson’s

Waterside Pottery – such was his skill as a thrower (Cartledge 2021). There is

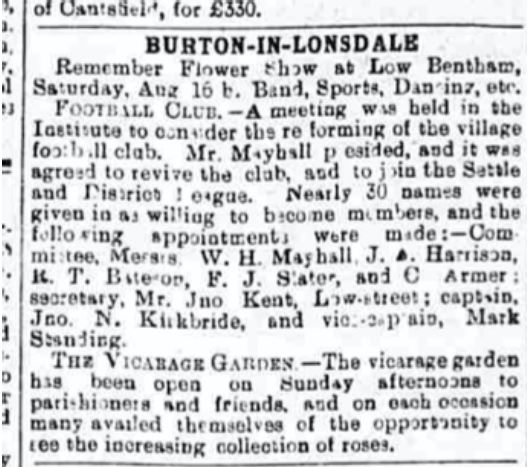

clear evidence that Freddie was living back in the village in 1919, as in this

year there is a newspaper report of him being appointed to the Burton-in-

Lonsdale Football Committee (see below Fig. 14), along side one

R.T.Bateson.

However,Town End Pottery, unsold in 1914, began to deteriorate to such an

extent that they became a concern for the Parish Council:

“Sept 3rd 1920

Dangerous condition of Town End Potteries.

Messers Saul and Woggott pay 1s. each for using waste land.

April 19th. 1922

The condition of Town End Pottery at the east end of the village was dangerous.

April 19th 1923.

At the pulling down of Town End Pottery the villagers be allowed to make use of

the materials to be sold.”

(SLA/11/1 BIL Council. Minutes of Burton-in-Lonsdale Parish Council, 1895-1923. includes

a section by R.T. Bateson listing the Burton men in the First World War.)

And so the pottery was gone.

With the demolition of Town End Pottery, Freddie and his family had to find a

new home. They moved from Burton-in-Lonsdale. By the autumn of 1923, the

Electoral Rolls show that Freddie and Margaret were living in Ireby. No

address is registered against their entry, just “Ireby”. According to Google

Maps, it is 2.4 miles from Ireby to Burton-in-Lonsdale. So maybe Freddie

cycled to work (presumably with his bicycle lights on) at Waterside Pottery

and back. They lived in Ireby until 1928 when they moved back to the High

Street in Burton-in-Lonsdale.

Strike Action ?

The 1921 Census return shows Freddie, aged 51, employed as a Thrower,

Brown and Stoneware at Wm. Bateson and Sons, Waterside Potteries,

Burton-in- Lonsdale. So what is the documentary evidence of him setting up a

union and calling a strike? The only secondary source covering industrial

action amongst the potters of Burton-in-Lonsdale is Lee’s book. He places the

strike as being sometime in the early 1920’s and states that it was a strike

about working conditions. His evidence comes from Richard T. Bateson’s oral

account of his time at the potteries, and although detailed, his is the only

account of the strike. It seems no record of the conciliation meeting

mentioned in Bateson’s oral testimony (Cartledge, 2021) at the Burton-in-

Lonsdale Sunday School has survived. Searches through the Allied and

Ceramic Workers Trades Union papers give no information specifically about

a strike at Burton-in-Lonsdale at this time. Because of large gaps in

newspaper runs (particularly the Lancaster Guardian), there is nothing in the

local or national press reporting this incident.

Crucially for Freddie’s history, and the strike at Waterside Pottery, the

‘Lancaster Guardian’ and other Lancaster papers like ‘Lancaster Standard

and County Advertiser, ‘ The Lancaster Gazette ‘ etc.which are a main

source for local news for Burton-in-Lonsdale, have very limited copies in the

fifty year period from 1870-1920. So there are no local newspapers surviving

for the years covering the Burton-in-Lonsdale strikes at Waterside Pottery.

There is evidence in local newspapers from other areas of the country about

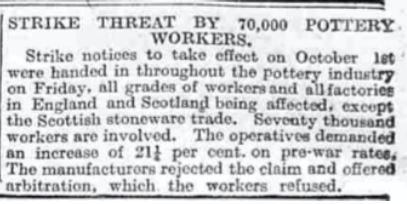

a National Strike of Pottery Workers in 1920.

This is from the Dorset County Chronicle and Somerset Gazette. September

9th 1920.

There is also evidence of strikes in Portobello from 1919-1920

Extract from Musselburgh News 2nd April 1920.

“Portobello Pottery Workers on Strike. Last Saturday the workers of the two Portobello

Potteries ( Messers A.W.Buchan&Co and Mr Wm. Richardson) came out on strike for a 20

per cent.increase in wages as from 9th October, 1919 . The workers are members of the

Stoneware Federation of Scotland (allied to the Ceramic and Allied Trades Union) and are

associated with the Glasgow district. The strike affects over 600 men of which 100 are

employed in Portobello. For the past six months negotiations have been going on, but up

to the present no amicable settlement has been arrived at. It is just a year ago since the

pottery workers’ last strike, when they were out for about four weeks before an agreement

was arrived at.”

There appears to be no documentary evidence for a strike at any of the

Burton-in-Lonsdale potteries the 1920’s, although clearly there was union

organisations shown by the earlier industrial action reported in the local

newspapers.

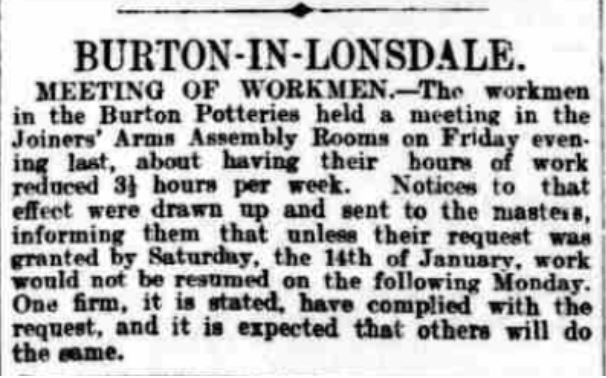

Strikes in Burton-in-Lonsdale Potteries.

The documentary evidence of organised action amongst the potters of Burton-in-

Lonsdale comes from 1899 and 1915. This entry comes from the ‘Lancaster

Standard and County Advertiser’ for January 13th 1899:

lll

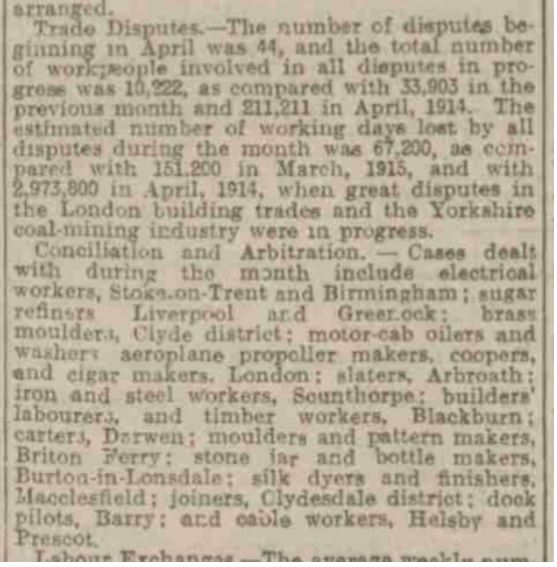

A further strike was organised at Burton-in-Lonsdale in 1915. Again, it is a

local newspaper from a different area, this time the Western Daily News for

18th May 1915, which has information about the Burton-in-Lonsdale Pottery

strike.

For some reason the newspaper carried reports from The Board of Trade’s

“Labour Gazette”, a report produced monthly giving very detailed information

about all industry, trade and production within the UK and Europe for the

Board of Trade.

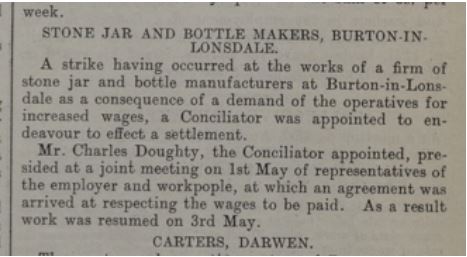

More detail about this 1915 Burton-in-Lonsdale strike is given under a

separate section of ‘Conciliation & Arbitration Cases and collective

Agreements. p. 165.(Labour Gazette, May, 1915)

So, clearly there was a strike of the Stone Jar and Bottle Makers, Burton-in-

Lonsdale in 1915, but this was a strike over pay, not working conditions and it

does seem unlikely that Freddie Slater was involved in this particular strike as

at that time he was probably working in Portobello. I have been unable to find

any evidence of the arbitration mentioned in the report, in the form of minutes

of the meeting, although the arbiter, Mr Charles Doughty does appear in local

newspapers from other areas of the country in his role as arbiter.

The 1915 Burton-in-Lonsdale strike can be explained by looking at the wider

national context. At the time of the strike, the First World War was having a

great impact on the structure of the labour market. The economy boomed as

demand for weapons, armament, self-sufficiency in food production etc, grew.

There was a labour shortage, as has already been illustrated. The

government and the unions presented a united front over the British War aims

and in 1915, the Munitions War Act was passed ( repealed in 1919) forbidding

strikes and lock-outs, and replacing them with compulsory arbitration. – hence

the entries in the Labour Gazette.

The forbidding of strikes and lock outs did not stop industrial action. These

disputes were generally over the war bonus. Whilst the economy boomed, the

cost of living rose so the government and trades unions asked for a war

bonus of 10% to be given. So:

“The potters began to press for an increase under the heading of ‘ war

bonus’ and in May 1915 they secured one across the board of 71/2 % . The

NEC (National Executive Council) of the union was given discretionary

powers to call immediate strike action – in conjunction with the Overmen’s

Society – at any firm which refused to pay the bonus.” (The Labour Leader

Year Book 1916)

This possibly explains the strike of the ‘Stone and earthenware bottle makers

Burton-in-Lonsdale’, the subsequent arbitration, and the settlement of pay, in

order for the men to resume work on 3rd May 1915.

What changes were made to wages and working conditions at the Burton-in-

Lonsdale potteries remains unknown, but ‘ Business began to decline

throughout the 1920’s….. By the 1930s business was really slow. … The

pottery went to a three day week for a long period during the early 1930’s.

Men were laid off, or just left for other jobs…… the pottery finally closed its

doors in 1933.” (Cartledge, 2021.).

Although, interestingly, for a pottery closing down, this advert for a Thrower

appears in The Derbyshire Times”, Saturday, May 21st 1932.

Maybe this is an advert for Freddie’s replacement?

Freddie – life outside the Pottery.

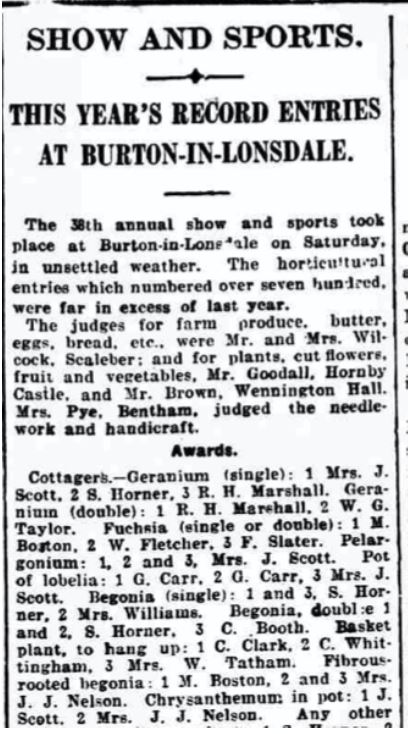

As children, the annual shows at Burton-in-Lonsdale and Bentham were a

highlight in the summer holiday calendar. We stopped slipping into becks and

racing around the hay fields to put on our best clothes and go to the shows.

Not that we knew anyone there, but our parents did and we relished the

atmosphere- the smell of the sheep, the flourishing of handicrafts, the size of

the prize onions and the garish bright blooms of the flowers in the

competitions. Burton show was always in mid August so we also managed to

earn some extra pocket money there by entering the sports competitions.

Little did we realise that we were following in the footsteps of the long held

traditions of the Slater family in entering such competitions.

The pub, the church, the chapel, the school, the parish council and the annual

show provided the social cement for villages in the nineteenth centuries – and

indeed continue to do so today. There is a long history of holding agricultural

and county shows across Britain. These events have been significant

community and economic events for rural villages.

For small villages like Burton in Lonsdale, the annual show was very much a

local affair, organised and run by volunteers from the village. It was an

occasion for everyone to meet, to show their products, to sit in the beer tent,

to exchange news. These shows had prizes for the best produce and the

winners were advertised in the local newspapers. Getting a good win at the

local show was one way of advertising your skill and showing that your

animals, or horseshoes etc. were better than anyone else’s. Nor was this

activity of showing your wares limited to the local show. Burton-in-Lonsdale

show did not have horse-showing competitions, so my grandfather, Freddie’s

younger brother, William Henry Garnett Slater entered competitions for

horseshoeing across the area. WHG Slater is recorded to have won 3rd prize

for the best shod light horse at the Lancaster Agricultural Show, with a

blacksmith from Cark-in-Cartmel coming first and one from Bentham, second.

( ‘Lancaster Standard and County Advertiser. 20th August 1909. Report on Lancaster

Agricultural show.)

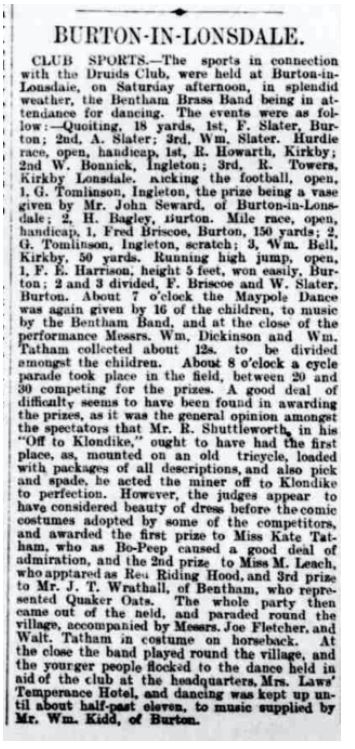

In addition to showing goods and produce, Burton show like many others had

competitions for sport, as indeed it did in our childhood – running, the high

jump, football and quoiting. These competition carried money prizes as well

as publicity and the extracts from local newspapers below show that Freddie

and his brothers were regular participants in these events. How much money

they collected doing this it is difficult to say, but it was one way of keeping a

high profile in the village before Facebook or Twitter publicised people’s

activities. Freddie and his brothers excelled at quoiting in particular. Their

occupations required high levels of strength and fitness, good hand-eye cooordination,

careful measuring and calculation and an eye for design, all of

which fed into their sporting abilities.

As well as winning in the quoting competitions, Freddie is seen to be

participating in helping the football club in which several of his brothers

played for the village (extract for 1919). By the time he was 59,(1929) his

quoiting days over, Freddie still enjoyed the competitions and won for his

fuchsias at the show in 1924. He wouldn’t have been happy with third prize.

Freddie wins at Quoiting.

The extract from the account of the Club sports held in Burton-in-Lonsdale in

1898 gives an idea of the range of activities for the day – the children’s

competitions, the Maypole dancing, the fancy dress and of course the

evening dancing.

From a report on Arkholme. Freddie wins at Quoiting. He also travelled

beyond Burton-in-Lonsdale to enter competitions. Arkholme is the village his

mother came from.

Freddie and his Fuchsia.

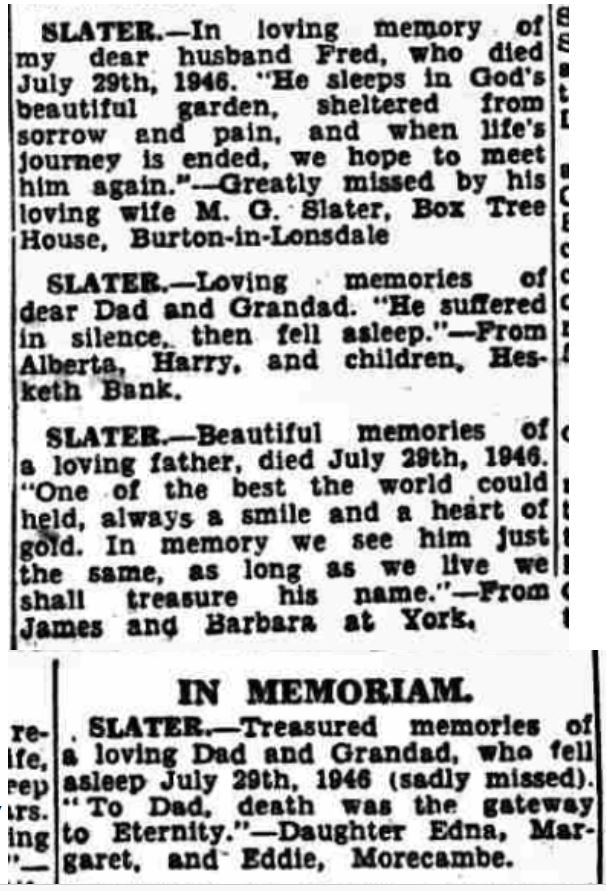

The last appearances of Freddie Slater in the official documents apart from

his death record in 1947, is his entry in the 1939 England and Wales

Register. He was 69, living with his wife Margaret, 60, at Box Tree House

Burton-in-Lonsdale. His occupation is listed as “Stone Bottle Thrower.

Retired”. He still retained his life-long identity as a potter.

Looking at his history has revealed the neglect of any discussion of working

conditions and organisation to improve them in the Burton potteries. Whilst

the pottery owners regarded Freddie as ‘ a strong unwieldy